PAUL SCHMITT WEIGHS IN ON 6 OF THE BIGGEST MYTHS ABOUT YOUR SKATEBOARD

How much do you really know about your ride? The Ride Channel talks with friend and skateboard expert Paul Schmitt (aka Professor Schmitt) as he breaks down six common assumptions one skateboard myth at a time.

( Article Originally Posted By Kyle DuVall 3 Mar, 2015 for the Ride Channel)

The skateboard media and industry do a great job educating skateboarders on what pro is doing what trick and who is wearing whose shoe. But when it comes to the quality of the boards they actually ride, skaters rely on a murky mix of supposition, experience, and the occasional bit of “conventional wisdom” from their peers or the old dude down at the skateshop. As important as they are to us, how much do we really know about our favorite plywood pals? And does what we think we know really line up with the technical realities? Get down to the bottom of each skateboard myth.

There’s no better man to ask than Paul Schmitt. “The Professor” has had a hand in almost every innovation in skateboard design for the past three decades. Over the course of his career, he has manufactured more than 10 million skateboards, both for companies in which he’s had a hand, Schmitt Stix, the New Deal, Mad Circle, and Element among them, and dozens of other brands from across the industry. You can spot them by the laser burn on top of them.

Schmitt’s dedication to his craft is all but unmatched. He routinely works one on one with skaters to design boards suited to their needs. And at 51, the engineer, entrepreneur, and manufacturer still skates himself. So he’s that much more invested in the sport and industry.

What, then, is really important about a skateboard? And what aspects of it do we neglect the most? How much of a role do pros play in designing their own shapes?

We put these questions and more to Schmitt, who had thought-provoking answers to all of them.

1. Skateboard Myth - Size and Graphics Aside, Popsicle Decks Are All the Same

The Professor’s Perspective: False

Just because all the boards on the skate shop wall look the same doesn’t mean they’ll ride the same. Popsicles, even those of identical size and materials, are not all created equal.

“Since the [Popsicle] shape became standard in the 90s, I’ve probably made 700 different Popsicles. They’ve all been a little different. The thing that makes the largest difference in how a board rides doesn’t have anything to do with the shape—it’s about the mold used and ultimately the leverage.”

There’s no simple measurement for leverage, and truck and wheel choice also play a role, but Schmitt has a simple method for judging the relative amount of leverage in the deck itself. He calls it the finger test.

“How many ‘fingers’ of flat are between the bolt holes and the place where the tail and nose kick up”—in other words, the number of fingers you can fit in those spaces—“will absolutely make the biggest difference in how your board feels,” he says.

The finger test. Photo by Paul Schmitt

The finger test. Photo by Paul Schmitt

That test so important because, all other factors being equal, it’s leverage that controls the balance between power and finesse in your setup. The more fingers of flat there are in a deck, the more control you’ll have. Fewer fingers, by contrast, means more power channeled into your pop, but less finesse. Because of this, identically shaped and sized boards can have radically different amounts of leverage depending on mold design, nose and tail lengths, and how they’re drilled.

“Muscles store energy, so the longer it takes your tail to hit the ground, the more energy is going to be released in your ollie and the more power you are going to have,” Schmitt says. “If you’re releasing all your energy in the ollie, you don’t have the energy to do the next part of the trick, whether it’s flipping your board or locking into a crooked grind.”

Different skaters, of course, have different needs when it comes to leverage. “If you’re an established pro, you have the skill to get power when you need it, so your primary worry is about finesse. But if you are just starting out, you need power. Having the finesse to do a manual doesn’t do any good if you can’t ollie up on the manual pad to do one”.

2. Skateboard Myth - Pro Skaters Don’t Design Their Own Decks, and Most Don’t Ride Them

Kyle Walker Photo by Vans

Kyle Walker Photo by Vans

The Professor’s Perspective: Partially True

Any business that uses celebrities to sell products will be dogged by the question of whether those celebrities actually use what they’re endorsing. Does Nyjah Huston actually eat those snack crackers? Are those cans up on the deck at Street League really full of Monster energy drink? When it comes to hardware, though, the question becomes more significant.

What the consumer wants drives design decisions brands and pros make. Schmitt cites two of today’s top pros, who shall remain unnamed, as examples.

“If you find one of their boards 7 7/8 inches wide or above, they aren’t riding it. These two guys have no problems with their 7 3/4 boards—but their brands can’t or won’t sell anything under 8 1/4. Salesmen and purchasing agents, not the pro riders, are making many of the decisions in these things.”

Is this a shady practice? Schmitt manufactures both the boards that wind up in the shops and some of the custom decks pros use in lieu said boards, and he doesn’t think so. “The problem is making the judgment from the wrong perception.”

In short, do skaters know what the pro’s name on the bottom of a board actually means?

The relationship between rider, brand, and the deck that gets pressed and sold can be impossible to figure out unless you know the pro personally.

“There are guys who don’t care and don’t want to bother with it. You can get a guy who comes into my workshop and just picks out a shape, or never comes in at all; they may be too busy with contests or demos or just skating,” Schmitt says. “Other guys come in and really look at other brands molds and concaves to get ideas, but the brand can’t sell the mold because it doesn’t fit their product line”

And some ride production boards straight off the shelf.

The brands, of course, always have a say, and in some cases they’re not interested in their riders’ input at all. Schmitt tells of one legendary pro skater who came to his shop recently. The skater in question was amazed by how much difference some fine-tuning could make in his deck, but he seemed doubtful that what he had learned would translate to his next model.

“He told me he just takes what his sponsor gives him,” Schmitt says. “He said at this point he doesn’t even bother to complain anymore.”

Time is a big factor in the discrepancy between what pros ride and what they push as well.

“Sometimes what sells is in perfect alignment with what pros are riding,” Schmitt explains. “I love it when pros are riding true production. Sometimes that’s the case, sometimes not. The pro is often ahead of what the consumer wants, but the distribution, retailers, and even consumers aren’t there yet. Eventually it always swings back and forth between what works for the pro and what skaters want.”

3. Skateboard Myth -The A Scale for Wheel Durometer Can’t Be Trusted

The Professor’s Perspective: True

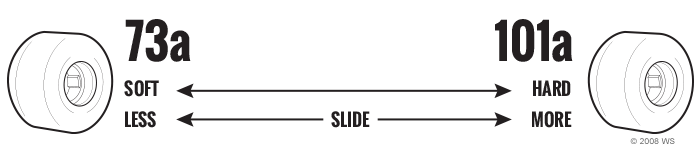

All groms learn early on about the good old A durometer scale: The higher the A number, the harder the wheel, which makes for faster speeds and better slides. Softer wheels, then, offer better grip and a smoother ride across rough terrain.

Or do they?

The durometer scale is a fine measure of soft wheels, but when it comes to today’s super-hard ones, things aren’t quite as straightforward.

“It’s pretty faulty,” Schmitt explains. “The A scale is maxed out at 100a. 101a isn’t even on the scale. It’s a marketing myth. Its easy for consumers to understand, but you can’t really validate it.”

When wheel durometer went beyond the limits of the A scale, brands worried about confusing consumers, so they didn’t want to switch to more accurate measures. “To tell the story, you need the B or D scale,” a completely different measure, Schmitt says. “But people can’t accept change. It’s way easier to accept 101A than 84B or 60D.”

The problems with the A scale go beyond numerical technicalities, though. “Push any scale to the edge and the accuracy is going to diminish at the ends of the scale,” Schmitt contends. This is why the grip/slip ratio between one brand’s 97As and another’s 99s can be all over the map. The A scale just isn’t precise enough at the extremes to represent variations in very hard urethane accurately.

Schmitt sees durometer as secondary anyway.

“Who cares about the hardness if the chemistry isn’t right?” he says. “Formulation and process control have a bigger effect on how a wheel rides than hardness.”

Those factors are why one company’s 99a wheels might outslide another’s 101as, or why you can have 101as that will grip harder than some of their softer rivals.

The bottom line when it comes to wheels is this: The only way to really find the best urethane for your particular needs is through the gradual (and sometimes pricey) process of trial and error.

4. Skateboard Myth - The Higher the ABEC Rating, the Better the Bearing

Photo: Bones Bearings

Photo: Bones Bearings

The Professor’s Perspective: False

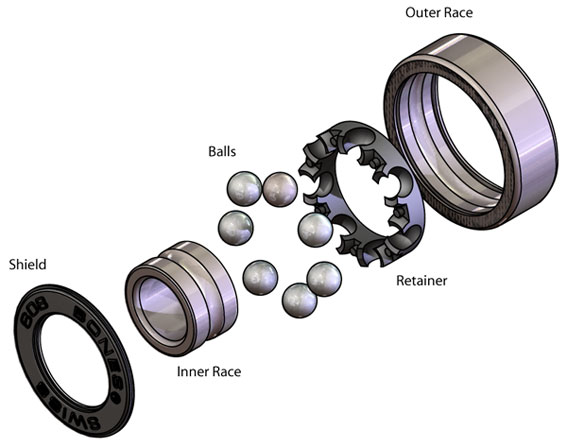

The ABEC (or Annular Bearing Engineering Committee, for the nerdier among us) rating on bearings is one of the few straightforward specs in skateboarding. If you believe the sales pitches, a higher ABEC means a better bearing (and, consequently, a higher price tag). But does an ABEC 6 rating really mean a bearing is better for your ride than an ABEC 4?

“In skateboarding, the ABEC rating is absolutely useless,” Schmitt says. “If you’re talking about a gyroscope in a Boeing 747 or a high-speed motor, then ABEC is going to make a difference, but in a skateboard, no.”

This is because the ABEC rating is actually meant to measure how bearings will perform under industrial conditions well beyond anything a skateboard will encounter. And it doesn’t even apply to the most significant stresses your board faces.

“ABEC doesn’t measure side pressure in a bearing at all. Every trick you do, every slide, puts tremendous side pressure on your bearings, so in a skateboard, things like the fit of the balls to the races, the materials in the shields, the tolerances, the cages, and the lubrication are all going to have a much bigger effect on how a bearing performs than the ABEC rating.”

Then there’s another issue: whether your expensive ABEC 7 bearings are actually ABEC 7s at all.

“There are Chinese factories that will put any number you want on a bearing,” Schmitt explains. “There’s no authority inspecting them at the border to make sure they are what they say they are. Honestly, we should just be glad they can produce bearings so cheap. When I buy bearings for the machines in my factory, they can run $10 to $20 dollars a piece.”

5. Skateboard Myth - Chinese-Made Boards Are Inferior to Those Manufactured Domestically

The Professor’s Perspective: Inconclusive, but plausible

You hear the phrase “China wood” thrown around a lot at the parks and skateshops. For some, the disdain for companies that outsource manufacturing to China is purely political. For others, the idea that Chinese factories cut corners and prioritize quantity over quantity is an unassailable truth. But is the “made in China” sticker on your stick the red flag some are certain it is?

It depends.

“People moved production to China because it was cheaper and they wanted to stay in business,” Schmitt says.

The Professor presently produces boards at his PS Stix factory in Mexico.

“I made boards in China for eight or nine years, and I had no trouble making boards that were up to my standards with my wood and with my glue from the U.S. But with my levels of training and my quality standards, ultimately I couldn’t compete with what other Chinese factories were doing, and other Chinese factories couldn’t afford to copy what I do. Ultimately, in China you are going to get the level of quality you pay for. Looks can also be deceiving. I just couldn’t afford to be in business in China with my standards. ”

Management practices in factories makes things that much more unpredictable. “A lot of bad board manufacturing practices that went away in the 1990s crept back in the 2000s,” Schmitt contends. “Heat curing boards”—that is, drying the glue that holds the plies in a board together by exposing it to high heat—“is one. No legitimate board manufacturer in North America hot cures decks.”

There’s also the question of the source of the raw materials used in the Chinese factory. “I’ve seen cases of factories claiming they’re using Canadian hard maple, but then you look at their manifests and you see their wood actually comes from Vermont, which is fine by my standards. Other times they’re using Chinese maple. Just because they’re putting a maple leaf sticker on the board doesn’t mean you’re getting Canadian hard maple. They will put anything on board that they think will help sell it.”

One aspect of overseas production Schmitt doesn’t worry about, though, is the shipping conditions on the long container ship rides from Asia.

“I did tests by putting sensors in containers,” he says. “The conditions really weren’t any different from what you got in a semi truck going around the world. There may be some variations in terms of where the container was located in the stacks of containers on the ship, but even those differences weren’t bigger than what you get between the inside and outside of a stack of boxes in a semi-trailer.”

6. Skateboard Myth - We’ve Perfected the Skateboard

Sculpture by Haroshi

Sculpture by Haroshi

The Professor’s Perspective: False

It’s true that none of the polymer and composite materials companies have substituted for wood veneers have ever been able to measure up to cold-grown maple in the eyes of consumers, but does this mean innovation in board construction is a thing of the past?

“I applaud anyone trying to to do anything new,” Schmitt says. “I’ve tried all kinds of materials, I’ve combined everything I can, and, in my opinion, there’s nothing better than hard maple.”

We’ve been using it for decades, but it’s hardly maxed out.

“There is so much you can do with seven plies of maple. Even with hard maple, there’s how you treat it, the thicknesses, and where you put it, but without a team rider accepting an innovation, a brand marketing it, and a consumer willing to pay for it, change will never take hold. ”

For Schmitt, these design and engineering X factors mean there is always room for innovation, even without considering experimental materials.

“So much of what I do, so much of creating a skateboard, has to do with concave molds. Using molds to distribute energy, to keep energy moving, that factors into everything I do. That’s what you have to do in a skateboard. The point where the energy stops moving in a board is the place where it breaks when stress is applied.”

So why aren’t brands and, especially, skaters more focused on innovation? It’s a complex combination of elements, some of which are consumer-driven.

“Skateboards have been at the same price point since the ‘70s,” Schmitt says. “People don’t want to pay a couple bucks more for a deck.”

Other factors are the result of brand-based marketing and economics. Brands don’t want to push new innovations when those innovations are the property of a factory that they may not use for all of their decks. That would lead to noticeable inconsistencies in the products they sell.

Either way, there’s a lot more that goes into making a good skateboard than most skaters want to talk about.

“The consumers are the ultimate judge of what comes to market,” Schmitt says. “Request what you want and vote with your dollars. The future of skateboarding will be guided by your actions.”

Learn more about Paul Schmitt’s CreateAskate.org board-making program